Designing Environments for Memory Care Residents: Part 1

What would it feel like to wake up and not remember who you are? Or, what if you feel the need to use the restroom, but don’t exactly remember how or where to go about it? Dementia is a frustrating disease for the person being affected, but also for the people that know and love them. Designing a dementia care home requires an understanding of the disease itself, how the architecture can affect residents’ daily routines, and how our designs can impact their lives in a meaningful way.

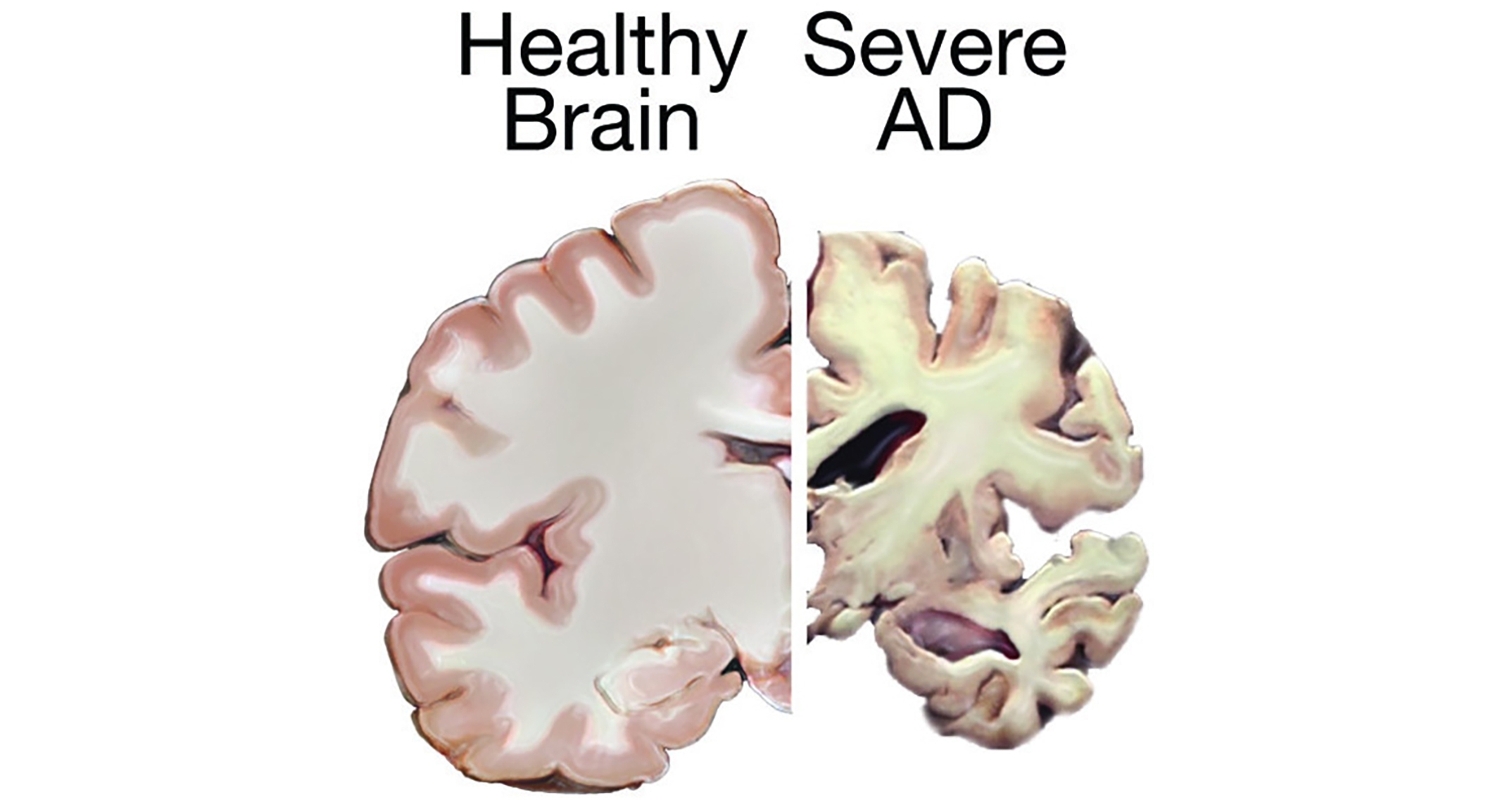

Alzheimer disease is a degenerative disease that leads to the gradual loss of memory, judgement, and ability to function. Image courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine

Dementia is a disorder caused by damage to brain cells, which interferes with the ability of these cells to communicate with each other. There are many different types of dementia, such as vascular, frontotemporal, and lewy body. However, the most common is Alzheimer’s disease. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, “Alzheimer’s disease accounts for 60-80 percent of dementia cases. The brain region called the hippocampus is the center of learning and memory in the brain, and the brain cells in this region are often the first to be damaged. That's why memory loss is often one of the earliest symptoms of Alzheimer's.”1

A large part of an individual’s sense of well-being comes from the ability to care for oneself. However, the loss of cognitive functions, new memory development, decision making, and emotional control can increase frustration, making daily life for someone suffering from dementia a challenge. Architecture can play a significant role in making simple tasks—that are often taken for granted—like bathing, dressing, grooming, eating, and finding your way around more instinctive through the environment itself. For example, providing a visual line of site from the bed to the toilet triggers the brain to remember where and how to use the bathroom. Utilizing simple wayfinding and signage is another way to maximize a sense of orientation for residents, since those suffering from memory loss may not be able to comprehend complex language. Paying attention to adjacency relationships and providing tailored accommodations, such as a smaller closet with fewer clothing choices, can decrease anxiety and maximize independence.

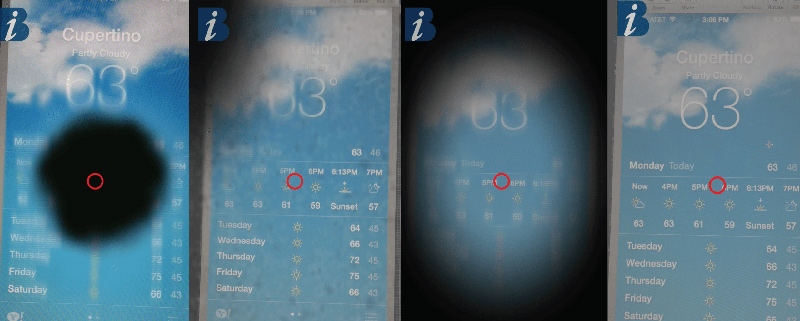

Tools like the VisionSim app can simulate age-related low-vision conditions, helping designers view the built environment through the eyes of someone with sight issues. Image courtesy of Smashing Magazine.

The aging eye cannot distinguish colors as well, can have difficulty focusing, and has decreased depth perception. Thoughtful interior design can make life less frustrating for residents when we take into consideration the abilities that are remaining. Making sure the chair arms and seat are contrasting in color to the flooring is a simple yet impactful technique to aid the resident in taking a seat easily. Using ample, even light rather than “mood lighting” provides visual stimulation and increases visibility.

Providing an environment that allows for self-care—versus trapping residents in a “child-like” environment that doesn’t recognize choices and abilities of an individual—creates a sense of self-worth that will bring joy to a resident. Design that provides ample physical support, as well as appropriate levels of stimuli (since people with dementia have a decreased ability to deal with multiple and competing stimuli), allows for greater levels of independence. This often results in a strong sense of accomplishment and fulfillment.

Deliberate use of color, simple wayfinding techniques, and amenities that that encourage self-care contribute to higher levels of independence and fulfillment. Rockwood South Hill Summit Tower — NAC

Being able to connect to nature and engage with the environment can bring meaningful value to a person. Gardens provide a place to sit and enjoy the sun on your face or have a conversation with the person next to you. An area in the garden where residents are allowed to plant seeds, and water and care for plants, may even evoke memories of their past gardens.

Gardens can have a powerful, positive impact on emotional and mental health by providing exposure to sunlight and a connection to nature. Healing Garden at Legacy Meridian Park Medical Center – Quatrefoil Inc. Photo by Naomi Sachs

Additionally, regular exposure to sunlight has a direct impact on an individual’s emotional state. Our internal clocks, which are regulated by circadian rhythm, trigger things like sleep, wake, and other daily patterns. Because of this, the brain needs sunlight to stay on the 24-hour cycle. Alternations in circadian rhythms can have a profound consequence on emotional behavior and mental health.2 An exterior garden enables residents to get “out” and get that sunlight. That same garden can also provide a safe and enclosed area for recreational exercise and space to wander. It can serve as a destination for self-discovery and meaning.

Dementia is a disorder that slowly takes away people that we know and love; providing a home for them that can enhance their abilities and bring joy to their life is something we should all strive to design. In future months, we would like to take a deeper look into the strategic and intentional design elements that can have a profound positive impact on the quality of life for those suffering from dementia and those caring for them.

References

1 Alzheimer’s Association, “What is Alzheimer’s?” Alzheimer’s & Dementia. Accessed June 8, 2018, https://www.alz.org/alzheimers_disease_ what_is_alzheimers.asp.

2 Ruth Benca, Marilyn J. Duncan, Ellen Frank, Colleen McClung, Randy J. Nelson, and Aleksandra Vicentic. “Biological Rhythms, Higher Brain Function, and Behavior: Gaps, Opportunities and Challenges.” Brain Research Reviews, 62(1), 57–70. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.brain...