For the Love of Nature! Introducing Biophilia in the K-12 Learning Environment

Connecting Natural and Built Environments

It cannot be denied that there exists a significant gap between the natural and built worlds. All too often, buildings are designed with a certain separation—the building itself is seen as one entity while its surrounding landscape is viewed as something entirely different. This chasm has negatively impacted both humans and the environment. A greater emphasis is placed on having the latest technology indoors; children in particular are caught up in this artificial, electronic world of technology. Sensory development in humans often begins with exposure to the outdoors and today’s children are losing out on this critical element of healthy growth.

Landscaped environment at Cherry Crest Elementary School, Bellevue WA - NAC Architecture

The Impact on Our Children

The positive effect of nature on children is a recurring topic in the writings on educational research. Countless studies reveal that direct exposure to natural elements has positive effects on a child’s ability to learn and grow. These studies, conducted in a variety of fields—from education to psychology to the social sciences—paint a broader picture of what has been learned:

- Richard Louv, author of the best-selling book Last Child in the Woods, cites studies of preschool-aged children in Sweden and Norway who played on either flat playgrounds or uneven natural grounds. After one year, the children who played in the more natural locations exhibited better motor skills than their counterparts.1

- Researchers found that children who play in areas primarily consisting of manufactured play structures as opposed to natural features establish a “social hierarchy through physical competence.” 2 Conversely, children have been observed to develop both cognitive and physical competencies when they have access to natural play areas.

- Researchers Scholz and Krombholz studied the effects of forest kindergartens, building-less schools located in outdoor settings that encourage children to explore their natural surroundings. They discovered that the motor performance of children from forest kindergartens was superior to that of children from traditional kindergartens.3

- Recreational researcher Alan Ewert studied the positive effects of outdoor programs. He concluded that participants showed positive gains in areas including self-image, coping skills, cognitive and intellectual performance, physical health, personal values, and interpersonal and social interactions.4

Despite a demonstrated need for a strong connection to nature, it remains a challenge for most schools to incorporate natural outdoor space in their programs. In particular, urban schools face the greatest challenge. When over 98,000 urban public schools serve over 49 million students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2014), this becomes everyone’s problem.

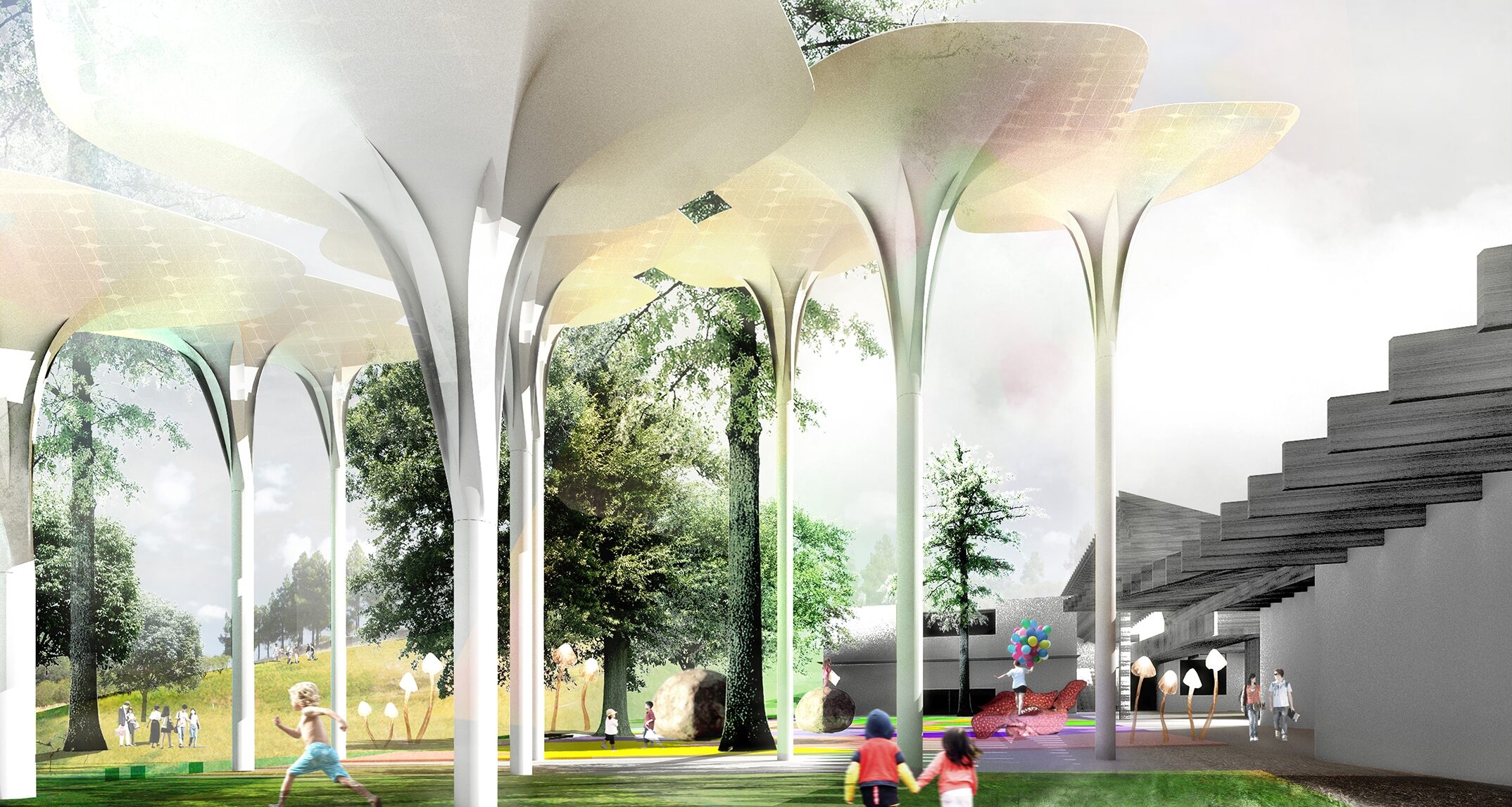

Solar mushrooms at Chatsworth Hills Academy, Chatsworth CA - NAC Architecture

Biophilic Design: Our Answer

Now that we know there exists a problem that must be addressed, just how do we go about doing such a thing? The answer is in our DNA.

In 1984, biologist and Harvard University professor Edward O. Wilson published his book Biophilia that coined the title term meaning, “the innate tendency to focus on life and the lifelike processes.” Etymologically, biophilia comes from the Greek “bios,” meaning life, and “philia,” meaning fondness. As a field biologist specializing in the behavior of ants, Wilson combined his scientific knowledge with his keen sense for the human condition, ultimately arriving at his theory of biophilia.5

Further studies and research involving biophilia have led to an entirely new field of design aptly named “biophilic design.”

Living Wall at Hazel Wolf K-8, Seattle WA - NAC Architecture

In 2008, Dr. Stephen R. Kellert of Yale’s School of Forestry and Environmental Studies published a book by this very title in which he stated that biophilic design is “an innovative approach that emphasizes the necessity of maintaining, enhancing, and restoring the beneficial experience of nature in the built environment.”6 Kellert’s own definition of biophilia, though similar to his predecessor Wilson’s, further expands the term to mean, “The idea that humans possess a biological inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes instrumental to their health and productivity.” With this elaborated meaning, Kellert acknowledged that this innate love of nature is actually an essential part of our development and maturation as a species, deeply embedded in our genetic code.7

It is this evolution as a species which illustrates the fact that, although this field seems like an inventive design approach, it is how humans have been designing for thousands of years.

Symbolic forms of nature have been seen in some of the oldest rock art and told in stories from the beginning of recorded time.8 Take the 14th century Moorish Alhambra in Granada, Spain where intricate plant motifs are carved into the stone walls, ceilings, and columns and outdoor courtyards and patios are interspersed throughout the complex. Then there is Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1950s-era Samara House in western Indiana, where the shape of the samara, the winged seed of a maple tree, is replicated in the design of the home’s windows and furnishings.9 Biophilic design has held a significant place in history without being formally recognized by name until quite recently.

Covered porches at The Wonderful Academy, Delano, CA - NAC

Incorporating Biophilic Design into Schools

So, how can schools incorporate elements of biophilic design into their plans? Various sources suggest ways to develop learning spaces to support a nature-based curriculum, as well as foster positive developmental responses from students. These include:

- The integration of outdoor learning areas allows for more exploratory, experiential education. When a variety of native species are incorporated into the landscape, a natural habitat can be established for a more beneficial learning experience.

- The use of clear glass over more translucent options allows for greater transparency between the indoors and the natural outdoors; the indecipherable shapes created by more opaque barriers become unnecessary distractions for children in classrooms.

- · For indoor materiality, not only should natural materials like wood be considered, but finishes that make use of symmetry and patterns, particularly those found in nature, are encouraged as ways of sparking inquisitiveness and problem-solving.

Natural building materials at Machias Elementary School, Snohomish WA - NAC Architecture

These features, along with more than 70 other biophilic design elements specifically detailed by author Kellert, greatly enhance the user’s experience of built space.10 NAC is no stranger to biophilic design principles, having incorporated many of them into some of our K-12 projects:

Environmental Features: bringing a bit of the outdoors in.

Two of the vertical panels of Hazel Wolf K-8’s Living Wall are independently set-up for light and water so that students can conduct investigations. One panel serves as the control while the other can have its features manipulated.

Exploration & Discovery: experiential learning strategies link lessons to the real world.

Hazel Wolf’s rain garden gives students the opportunity to explore important questions: What types of plants and animals use this water filtering feature? How does it change over time? How does a rain garden filter rainwater?

Views & Vistas: witnessing the activities of the natural surroundings develops a greater awareness of and appreciation for the environment.

At Mt. Si High School, strategically placed windows offer multiple views of the outdoor environment from just about any point inside the building. This will lead students to inquire about the natural shifts they observe on a daily basis, leading to student-driven investigations.

Biomorphy: built forms resemble the organic.

At Chatsworth Hills Academy, “solar mushrooms” link nature to the built environment by replicating biological shapes and figures in designed elements.

Information Richness: sensory environments challenge the intellect.

An instinctive connection to the natural world is reiterated in the textured wall coverings throughout the corridors and common spaces at Mt. Si High School. These will inspire curiosity, imagination, and discovery in students.

Bounded Spaces: a sense of security in the outdoors.

Landscaped exterior areas are interspersed throughout the built structure at Cherry Crest Elementary School, offering the opportunity to experience the outside environment while still providing feelings of safety and protection.

Natural Materials: blurring the line between interior and exterior.

Natural building materials are used both inside and outside at Machias Elementary School, breaking the traditional definitions of building versus landscape.

Inside/Outside Spaces: bridging to the adjacent topography.

The Wonderful Academy’s covered porches surrounding the second floor create a sense that the exterior environment is connected to the interior learning spaces. This move signifies the blending of landscape with culture.

Learning Courtyard at Hazel Wolf K-8, Seattle WA - NAC Architecture

The significant amount of scientific research on the topic of biophilia in education clearly illustrates that a strong connection to nature can enhance student development. From cognitive to affective to social outcomes, the benefits are numerous and cannot be discounted. Let us continue taking steps to craft as many opportunities as possible for students of all ages to engage beneficially with the natural environment.

References

1 Richard Louv, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2005): 48-49.

2 Richard Louv, Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature-Deficit Disorder (Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2005): 88.

3 Diana E. Bowler, Lisette M. Buyung-Ali, Teri M. Knight, and Andrew S. Pullin, “A Systematic Review of Evidence for the Added Benefits to Health of Exposure to Natural Environments,” BMC Public Health (2010): 456.

4 Stephen R. Kellert, Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-nature Connection (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005): 16.

5 Edward O. Wilson, Biophilia (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1984): 1.

6 Stephen R. Kellert, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008): vii.

7 Stephen R. Kellert, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008): viii.

8 Stephen R. Kellert, Building for Life: Designing and Understanding the Human-nature Connection (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2005): 66.

9 Stephen R. Kellert, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008): 41.

10 Stephen R. Kellert, Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science, and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2008): 6-15.