Get Out! The benefits and opportunities of outdoor education

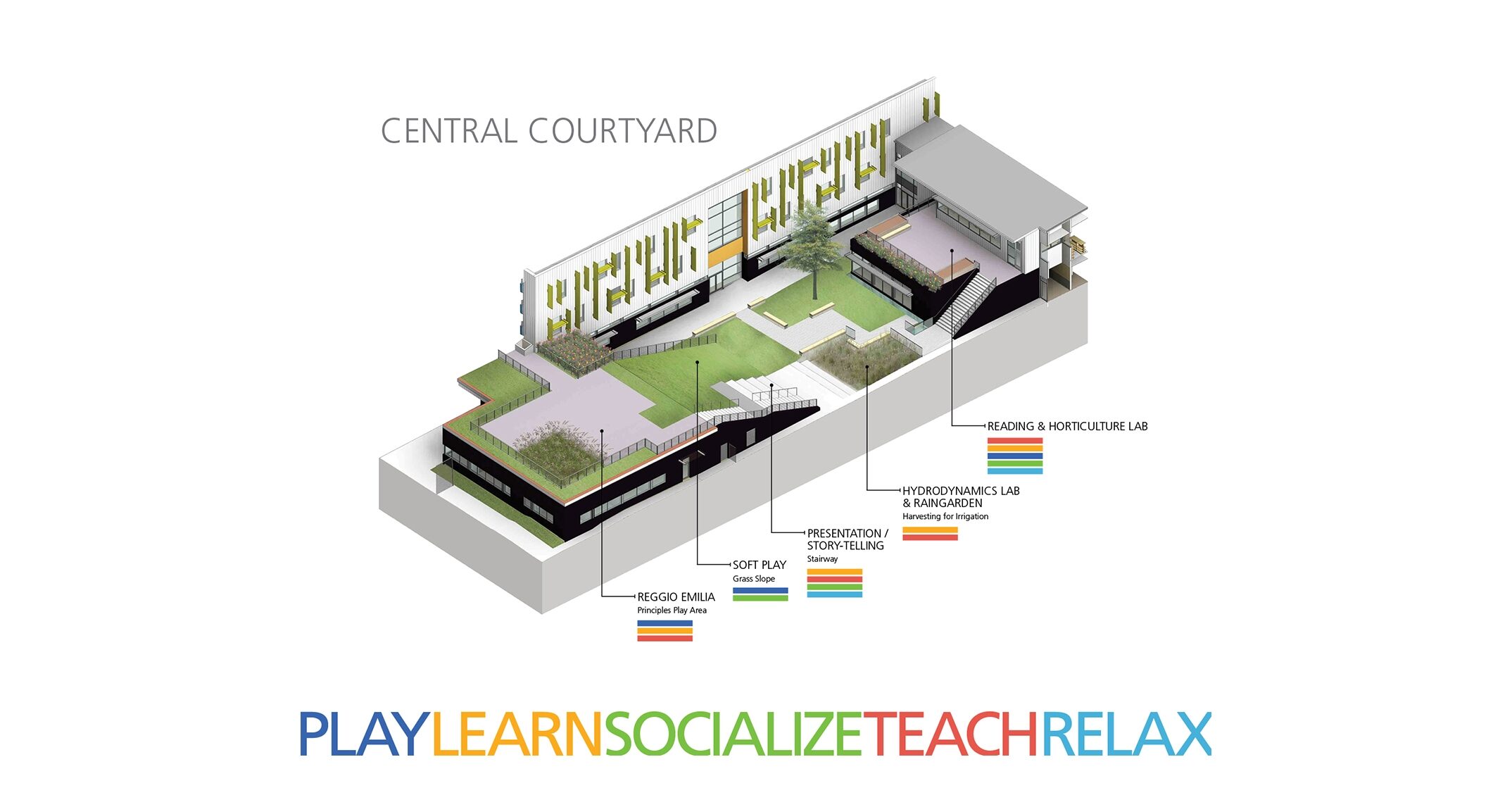

Cherry Crest Elementary School, Bellevue - NAC Architecture

We know that in order for our students to be able to succeed in career and life beyond grades K-12 our education system can no longer emphasize the transmission of pieces of information that are memorized and then tested. Twenty-first century education should have a bias towards action – hands-on learning, experiential learning, interactive teaching. This approach would more adequately prepare students for what is expected of them in the 21st century work place.

So, where do we begin?

One step is rethinking our pedagogical methodologies. Twenty-first century learning needs to make the transition from primarily stand-and-delivery teaching to a learning environment where teachers are chiefly mediators of the learning process, helps students to take control of their own learning, and gives students and teachers the opportunity co-create knowledge. Let us be clear - we are not advocating for the abolishment of “teaching by telling.” There are still instances where this practice can be very effective. We advocate for complimenting classroom time with out of doors learning.

When the formal learning process is moved from the traditional classroom and into a natural environment the benefits add up to a big impact on student learning. Whether guided or open-ended, students bring a wealth of knowledge and curiosity to outdoor learning. The natural world empowers students to ask questions about what they notice and the tenacity to find the answers. Lesson plans cannot be written to the depth of learning that can take place when a student experiences a connection with the complexities of the natural world.

Hazel Wolf K-8 School, Seattle - NAC Architecture

What we know is:

- Natural environments, such as parks, foster recovery from mental fatigue, stress, and anxiety and are found to be restorative.1, 2

- People have a more positive outlook on life and higher satisfaction when in proximity to nature.3, 4

- Observing nature can restore concentration and improve productivity.5, 6

- Natural play settings have been found to reduce the severity of symptoms of children diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and improve concentration.7

- Exposure to natural environments enhances the ability to recover from illness and injury.8

- A direct experience with nature can provide greater interest in topics introduced indoors triggered by experience that was relevant, real-world, and tangible.9

- Play with natural elements (e.g., sticks, leaves, stones, sand, mud, etc.) was found to engage children longer than traditional play materials, supporting greater cooperation and pro-social behaviors.10

- Garden-based learning programs have resulted in increased nutrition and environmental awareness, higher learning achievements, and increased life skills for students.11

- Participation in outdoor school has been linked with higher ratings of conflict resolution skills, improved self-esteem, problem solving skills, and environmental behaviors.12, 13

- · Fieldwork has been linked to positive impact on long-term memory due to the memorable nature of the fieldwork setting.14

Hazel Wolf K-8 School, Seattle - NAC Architecture

So, why is learning in a natural environment so effective? Perhaps it's because moving education outdoors taps into the way people learn.

Learning is both a physical and social process. James E. Zull, professor of biology at Case Western Reserve University, found that learning actually alters the brain by changing the number and strength of synapses. “The changes occur when the teacher and learner, together, engage four essential parts and associated processes of the brain:

- Sensory cortex (which takes in new information through the body's five senses)

- Integrative cortex (which conducts reflective observation by comparing new information with old information in memory)

- Frontal cortex (where abstract hypotheses are formulated)

- Motor cortex (which actively tests hypotheses through physical actions such as speaking and writing, which elicit feedback from others, and thus, new information that enters the brain through the sensory cortex)

All four parts must be stimulated for learning to take place.”15 What Zull describes is the experiential learning process.

Taking learning outdoors is inherently experiential, and when it's properly conceived, adequately planned, well taught and effectively followed up on outdoor education paves the way for the ultimate teachable moment.

Outdoor education should not be viewed as something that occurs outside but a venue for students to apply their knowledge in a personal and meaningful way. Everyone involved in shaping education should understand this connection and work together to bring the outdoors inside as well as bringing the inside to the outdoors.

Cherry Crest Elementary School, Bellevue - NAC Architecture

What can architects do?

It is more important than ever that we create inspiring learning environments. Purposefully designed outdoor areas can help us create a specific sense of place for each school, and establish opportunities for teachers to enhance curriculum through real life science and hands on learning. There is plenty of evidence indicating that outdoor activities can trigger enhanced curiosity and connection making in students. We have seen outdoor students' explorations lead to completely unscripted connections with indoor lessons, sparking future inquiries. Interaction with nature has serendipitously triggered students' self-directed learning, forming a significant step where students take greater ownership of their self-initiated education.

There are different design concepts that help create successful

outdoor learning environments. Sometimes schools try to create their own new

eco-systems. The Primary School for Sciences and Biodiversity in

Boulogne-Billancourt, France intents to create a new eco-system in a dense urban

setting, both via green roof terraces with rich planting diversity and the

envelope that is designed to establish nesting places for a variety of birds.

Other times schools are integrated into a thriving existing eco-system. Valle

Alto Ecological High School in Valle Alto, Monterey, Mexico likewise has been

very careful to find its place in a rich eco-system without losing a single

tree. In Bellevue WA, USA, Cherry Crest elementary school gently sits in a

wooded setting, reinterpreting former storm rain drainage into a new design.

Green roofs lead to rain chains leading to a courtyard creek, leading to a

natural ravine on the site. Green roof, courtyard creek and chains, and

overflow rocky ravine all present ultimate teaching moments. Cherry Crest example

shows how a memory of an essential natural element can be a starting point for

creating a multitude of outdoor learning opportunities, and thus enabling

enrichment of the curriculum.

Farming Kindergarten, Biên Hòa, Dong Nai, Vietnam - Vo Trong Bghia Architects

In general, interpreting a memory of a former natural setting can be a very powerful design approach towards creating a stimulating outdoor learning environment and establishing a meaningful sense of place, rooted in its context. The Farming Kindergarten in Bien Hoa, Dong Nai, Vietnam uses continuous walking roof areas for gardens and planting lessons, evoking the former agricultural character of the area. Here the memory of nature is a generator for creating a wonderful sense of place, reflective of the transformations in a broader society. The Chrysalis Childcare Center in Auckland, New Zealand symbolizes the nation's bi-cultural character through two large trees, an English oak and a native Pohutakawa, equal in size. The design evokes an appropriate image for the multi-cultural facility. The c-shaped building forms a protected site area where the two trees represent nature as artifacts with deep cultural meanings. The whole courtyard is a playing and learning environment, where outdoors is as important as the interior classrooms.

Outdoor spaces are a very effective component to 21st century learning strategies. Student outcomes can benefit greatly by exposure to purposely designed outdoor environment and curriculum.

References

1 Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan, The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989).

2 Terry Hartig, Marlis Mang and Gary W. Evans, “Restorative Effects of Natural Environment Experiences,” Environment and Behavior 23, no.1 (1991): 3-26.

3 Fracnes Kuo, “Coping with Poverty: Impacts of environment and attention in the inner city,” Environment and Behavior 33, no.1 (2001): 5-34.

4 Phil Leather, Mike Pyrgas, Di Beale and Claire Lawrence, “Windows in the Workplace: Sunlight, view, and occupational stress,” Environment and Behavior 30, no.6 (1998): 739-762.

5 Tennessen and Cimprich, “Views to Nature: Effects on attention,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 15, no.1 (1995): 77-85.

6 Andrea Faber Taylor, Frances Kuo and William Sullivan, “Coping with ADD: The surprising connection to green play settings,” Environment and Behavior 33, no.1 (2001): 54-77.

7 Ibid.

8 RS Ulrich, “View from a window may influence recovery from surgery,” Science 224, no.4647 (1984): 420-421.

9 Louise Chawla, Kelly Keena, Illene Pevec and Emily Stanley, “Green schoolyards as havens from stress and resources for resilience in childhood and adolescence,” Health and Place 28, no.1 (2014): 1-13.

10 Ibid.

11 Cornell University Cooperative Extension and Department of Horticulture, “Highlights from Journal Articles,” Cornell Garden-Based Learning: Resources for gardeners and educators, October 1, 2015, http://blogs.cornell.edu/garden/grow-your-program/research-that-supports-our-work/highlights-from-journal-articles/.

12 American Institutes for Research, “Effects of Outdoor Education Programs for Children in California” (report, Palo Alto, 2005).

13 Caprara, Barbaranelli, Pastorelli, Bandura and Zimbardo, “Prosocial foundations of children's academic achievement,” Psychological Science 11, no. 4 (2000):302-306.

14 Justin Dillon, Mark Rickinson, Kelly Teamey, Marian Morris, Mee Young Choi, Dawn Sanders and Pauline Benefield, “The Value of Outdoor Learning: Evidence from research in the UK and elsewhere,” School Science Review 87, no. 320 (2006): 107-111.

15 James Zull, The Art of Changing the Brain: Enriching the practice of teaching by exploring the biology of learning (Sterling: Stylus Publishing, 2002).