Holistic Wellness: What We Can Learn from Native American Healthcare Practices

It’s April of 2019, which means we are midway through the first decade of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). It’s an appropriate time to reflect on the changes we have seen in the healthcare landscape, and what the possibilities are moving forward. One of the big advances that the ACA has brought about is a broader view of overall health; evaluating the effects of lifestyle choices, mental, and physical health not only on the individual, but how these factors impact the community at large.

Of particular interest to us design practitioners is understanding how the environments we create can better serve these types of healthcare models. Are there existing organizations that have already addressed some of these issues that we can study and learn from? A good place to start is with the philosophy and beliefs behind Native American health and wellness.

The mission of the Indian Health Service is to “raise the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level.” And much like the aim of the ACA, their goal is to promote the health of tribal members and their communities, while honoring and protecting their cultural history. Following are two examples that emphasize the key elements of a successful Accountable Care Organization and some key takeaways.

The Nuka System of Care

Nuka is an Alaska Native word that means “strong, giant structures and living things.” The Nuka System of Care has been practiced by the Alaskan nonprofit organization Southcentral Foundation for more than 15 years. The system is Native-owned and patients are ‘customer owners,’ given a role in designing and implementing services. This model centers on each customer owner’s unique story, values, and influencers to engage and support long-term behavioral change. There is a focus on trusting relationships that extend beyond clinical tests, diagnostics, exams and procedures. Nuka emphasizes that the most important health decisions are the lifestyle choices made outside of the clinical environment.

The Marimn Health Medical Center (formerly the Benewah Medical Clinic) incorporates architecture and detailing that references the tribe cultural and historical precedents. — NAC Architecture

The central public area inside the Marimn Health Medical Center was designed to serve as a place of gathering and celebration. — NAC Architecture

Marimn Health

Marimn Health offers a similar model to the Nuka system, focused on promoting wellness and holistic healing to all members of the community. Marimn is from the Coeur d’Alene language, based on the verb “marim,” meaning “to treat.” The organization’s medical and wellness centers serve Native American and non-native patients in Idaho, Washington and Montana, regardless of ability to pay. Marimn Health is an integral part of the community’s health; they do not turn away anyone or deny them service, and fees are charged on a sliding scale.

Supporting These Models through Design

So how do these models affect the built environment? What can we learn from them that can be applied when designing for non-Native healthcare delivery models? Perhaps the most important aspect of the two examples above is that the design of their facilities incorporate both cultural and symbolic references that resonate with their users. Both provide opportunities to integrate outdoor spaces with the interior environments, whether through access to courtyards and gardens or by creating a visual connection to the natural landscape. Centralized public spaces provide places for the community to come together and celebrate the culture and traditions of the tribes. These references serve to tie the facilities to their ‘place,’ making them relevant and welcoming for both the visitors and their care teams.

Secondly, in offering complete health services—clinical, mental health, specialty care, and dental—all under one roof, the patient can easily get a physical, followed by specialty testing, and fill a prescription all in one stop. This full-service approach also provides a more robust continuum pattern of care, particularly for rural patients that may be traveling substantial distances for services.

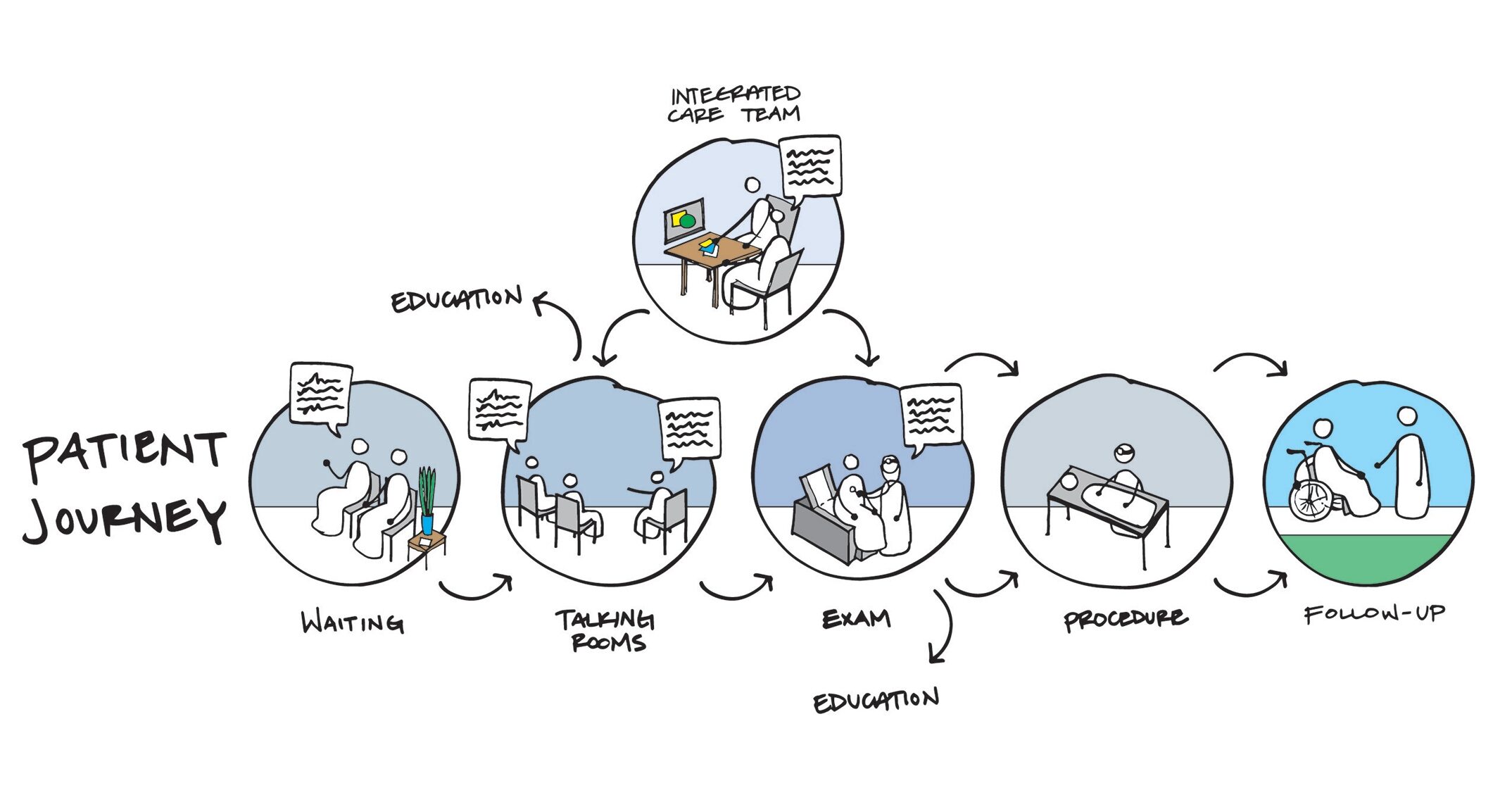

Clinical planning for these types of care models utilizes zones of care that improve patient flow through the facility and ensure they are only exposed to the level of interaction and treatment that is appropriate for their specific condition.

Clinical planning is also affected by these types of care models. In the Southcentral Foundation (SCF) example, one sees early adopters of fully-integrated care teams working in one open area. This encourages collaboration and communication between providers to fully understand the history and condition of each customers. SCF also utilizes ‘talking’ rooms as the first point of contact. These areas are non-clinical and serve as a place to sit down and have a one-on-one or family-based conversation in a low-stress environment that encourages interaction. The medical planning is then laid out for the customers to move from the least acute treatment to the more acute. In this way, they are only exposed to the level of treatment that is appropriate for their specific condition.

Finally, both models stress education as an ongoing part of wellness and wellbeing. Provisions for accommodating this are built into the environments throughout in the form of kiosks, information desks, and classrooms. Thus, the transfer of information and self-awareness is part of the ongoing lifestyle of the patients and their families.

The pathway toward the talking rooms in the Southcentral Foundation Primary Care Center provide daylight and views to the outdoors, while materials and finishes support further references to nature. Image courtesy of NBBJ.

Conclusion

We are already seeing a number of these strategies moving into the mainstream of current non-Native clinical planning. Collaboration spaces for care teams are starting to take the place of private offices. Clinical and behavioral health services are being offered under one roof. Community spaces are being provided for education and outreach. As healthcare moves forward in embracing holistic care, I anticipate that we will see more change. With clinics and care organizations becoming more community-based there will be opportunities for robust education and relationship building. Serving mental health needs as part of clinical care tends to destigmatize it and better serve behavioral health needs. As healthcare becomes more holistic, more transparent, and more educational, the communities served become better equipped to understand how they can define their health through lifestyle choices and preventative care.