Students Living Without Permanent Shelter

NAC is currently designing a school that includes a large percentage of students from families experiencing homelessness. At times, the percentage of students living without permanent shelter can reach 25%, and the total transient rate at the school can near 50%--transient rate refers to all students who may move in and out of the school within an academic year and includes students from families that secure temporary shelter but move regularly for employment opportunities. At this school, 50% equates to approximately 100 students. Despite these housing hurdles, this school manages to thrive. Within a tight community, those connected to the school have built a safe learning environment that inspires students to realize their potential; everyone is linked to an optimistic vibe that squashes pessimism. Here, students are not identified by their living status, in fact, a conscious effort has been made to remove all labels. As architects, we are inspired to design a new school that exemplifies education equity and wellness.

To determine the needs and wants of our project’s young learners, we regularly visit the school. Our discussion notes are below. The first-hand accounts we’ve collected from talking to students, teachers, and parents, have greatly swayed our design and have been the catalyst for this project’s progression. Also below are images of possible design solutions from past projects.

What do the students, parents, and educators need in a school?

One student brings a blanket to class. The teacher can tell when the student is anxious or overwhelmed when she pulls the blanket over her head. She uses it to shield herself from the outer world. With the blanket formed around her like a cocoon, she creates a personal and quiet place for herself to recharge. Understanding this student’s need, and similar privacy needs of her classmates, our team plans to add small alcoves around the building for students to sit in or crawl into. These nooks will offer young learners a private space to take temporary breaks from group activity.

Another student is regularly restless and acts out in class. When this happens, the teacher allows the student to leave the classroom so that he can freely move and vocalize away from others. To assist students like this, the teacher we spoke to suggested adding a defined common area outside the classroom with sound dampening glass. This will allow visibility of students while they take a break and express themselves.

An outdoor garden at Playa Vista Elementary in Los Angeles, California - NAC

A nook at Lake Stevens Early Learning Center in Washington state gives students an alternate place to learn and recharge. - NAC

A nook at Lake Stevens Early Learning Center in Washington state gives students an alternate place to learn and recharge. - NAC

A learning and reading space at Bennett Elementary School in Bellevue, Washington, gives students a tranquil place to take a break. - NAC

There was also a comment from a young student who told us: “I don’t want to make friends. I’ll just move and lose them anyway.” In response, our team is adding a variety of learning spaces within classrooms to support small group, project-based learning. Students like this are drawn to small groups, where they can work with other kids, but without the pressure of making friends. Students with trauma and housing instability tend to be withdrawn. Creating spaces on the edge of the activity allows them to feel safe and to connect to others in a more comfortable way.

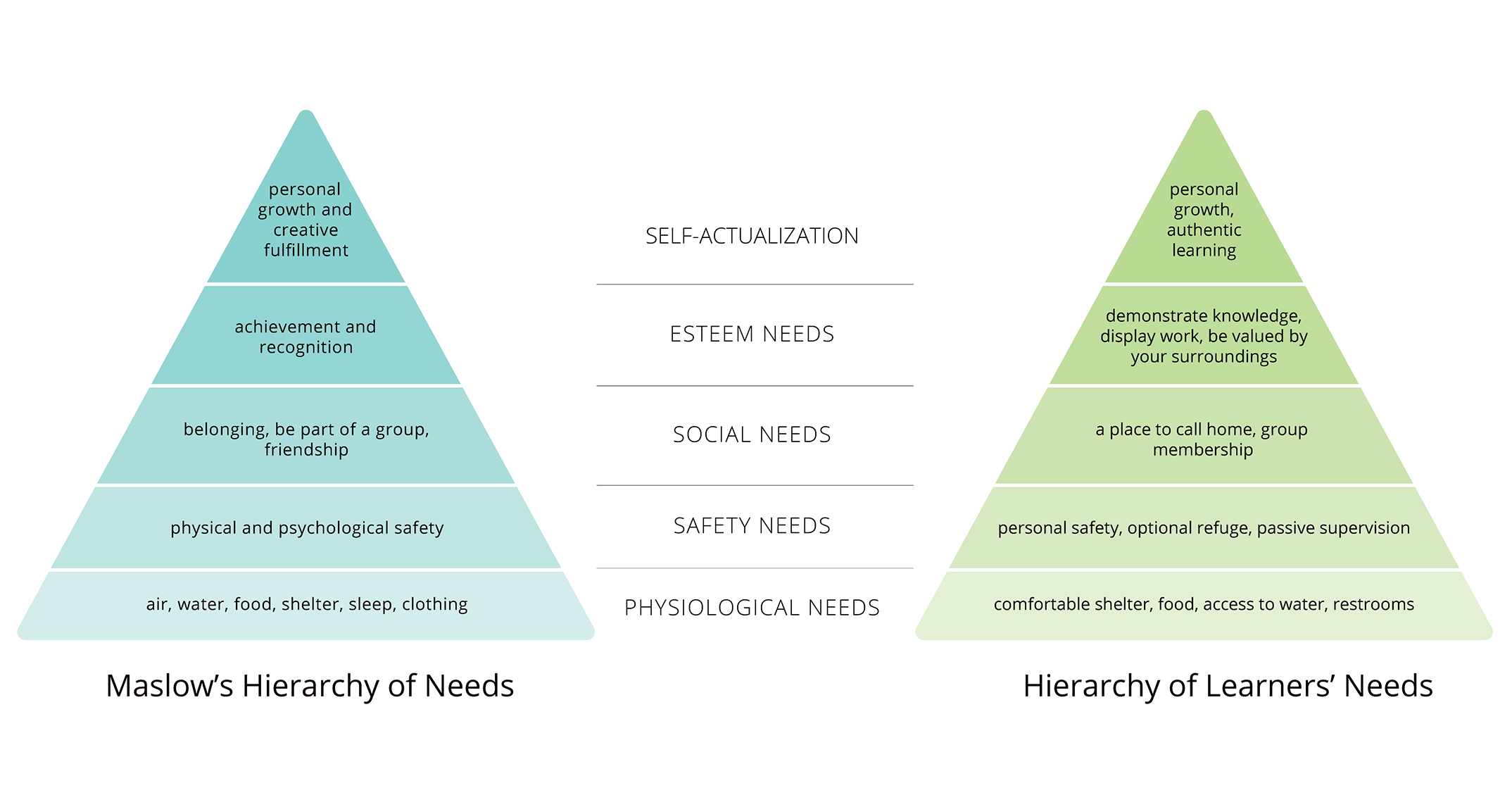

At this school, there is a focus on love and belonging, which is wonderful of course, but as architects, we also understand how important it is to address the physiological and safety needs as well, so that the students are ready to receive the offer of belonging. For homeless and transient students, basics such as food, shelter, clothing, sleep, and clean water are not guaranteed.1 Without these basics, students are typically too preoccupied worrying about survival to concentrate on schoolwork. This is especially true for food insecure students who are always worried about where and when they will get their next meal. Conventional routines connected to food are important. The preparation of meals, the consistency of scheduled food breaks, and the habit of eating together as a family are all comforting practices. In addition to food, students also worry about the safety of their belongings.

Storage is a primary need and very important to both students and parents. Students requested storage for school supplies and personal items. We are told students may bring everything they own to school, and therefore, keeping belongings safe can be a distracting priority. In response, we’re considering adding large lockers to provide personal storage separate from the standard book lockers most students will get. These personal lockers will be in a discrete place, away from common areas, so that locker owners are not made to feel on display. From talking to school leaders, even seemingly simple items like a toy car can mean a lot to a little one living with the bare minimum. After all, the things you can control, including the treasures that can be kept safe in a small hand or stashed in a pocket, those things don’t go away, but people do. Students can feel as though they are perpetually leaving someone. For these students, keeping that sense of control becomes a large part of their personal security—another basic human need. Inanimate things can serve as a steady constant for a child. It’s the comfort felt in object permanence, or, the insurance knowing something exists even when it’s out of sight. For this reason, safe storage is vital.

What do the students, parents, and educators want in a school?

Our team has been equally moved by what the students, parents, and teachers want from their new facility as we are with the number of things they haven’t asked for. Their needs list is modest. Here are some of their suggestions:

- An outdoor garden at Playa Vista Elementary in Los Angeles, link to project page

- An outdoor garden at Playa Vista Elementary in Los Angeles, CA — NAC Architecture

Students asked for:

- An atmosphere that feels like home.

- Places to retreat, such as private nooks or drop-in space connected to classrooms.

- Outdoor area to play with grass and sunlight. These students typically don’t have yards.

- Light. They asked for large windows and transparent partitions to keep the space bright and to stay connected to the outdoors.

- An overall calm environment that incorporates nature.

- A fun space that inspires imagination and discovery.

Parents asked for:

- A “family room” that is separate from the administrative main office area with resources for parents.

- Family space with accommodations for young children, such as a small toy area and multilingual library.

- Computers and internet access for both parent and student use.

- A small conference room for confidential phone calls or meetings with social workers and school staff.

- A comfortable place to fill out forms.

- A place to be out of the rain while waiting for their child.

- A space different from a classroom or office area. They want a place that is “theirs” where they feel welcome. It was noted that the administration area can feel intimidating to people who have been marginalized.

- Discrete access to clothes and food distribution.

The community room at Lake Stevens Early Learning Center in Washington state provides family space with toys and books, along with comfortable seating and an area for meetings. - NAC

Educators asked for:

- Learning and reading space.

- Tranquil space that supports a peaceful and nurturing environment.

- A quiet area for staff to recharge.

- “Little free neighborhood libraries” dispersed throughout the school where students are free to take or leave a book.

- Garden space. Gardening and outdoor activities tend to equalize students, regardless of their language of origin or living situation.

Onward. Phase two begins.

Our team is now moving on to phase two. We’re taking the input noted above and applying the feedback we’ve gathered to a building that we hope will ease the burden of those experiencing temporary housing challenges. As architects, we know how important it is to develop design solutions that support the activities of these young learners and provide a variety of environments that help the students and teachers navigate their day. As we move into phase two, we now have the opportunity to meet the needs of our neighbors by giving these children a quality, healthy, and nurturing place to learn. It is our shared belief that every child deserves to feel safe and valued, and every child deserves to be happy.

References

1 Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Human Needs. Source: https://www.simplypsychology.o...