Supporting Students to Thrive: Part 3, Using Research to Measure Effective Change

As highlighted in Supporting Students to Thrive: Part 2, schools have evolved to provide more than education. They also supply a sense of community, a place to access emotional and behavioral support, and a lifeline for families in need. It’s a heavy load on our schools. This expanded role often surpasses school resources, both in terms of budget and facilities. However, re-imagining the traditional education-centric approach to schooling is a gamble that makes many community leaders, educators, and parents squirm. Even as they recognize the need for these services, deciding how to incorporate them in the educational setting is unique to each community and school district. They question how best to incorporate the programs into the school day, how adding resources like new staff and modifying the built environment will impact already strained budgets, and how success will be measured. The stakes are high when it comes to decisions about education and mental health for our youth, and the outcomes of these decisions are sometimes not seen for years or decades. How can we ensure that we are truly combating loneliness, mental health, and low academic scores? How can we ensure students are truly connecting and engaging in the school environment?

Glover Middle School, a research case study

For the community and stakeholders at Glover Middle School, targeted data collection and research helped measure the effectiveness of design and program decisions in supporting students’ needs.

Serving one of the lowest socio-economic zip codes in Washington State, Glover Middle School was ready to turn the page on their 1960’s traditional building that could no longer support the current student culture and needs. With 70% of students coming from low-income homes, administrators and teachers were adept at providing targeted academic and behavioral support, against the tide of a building that was not set up for connection or community. The design process began by establishing connection and engagement as the foundational tenets for the new building. The conversation quickly turned to how success might be measured. How would the team know that solutions, such as transparency, operable walls, varying scales of spaces, and furniture choices in the new building, would be a remedy for the problems dogging the original middle school? This set our design team on a path to develop research methodology to measure some of these metrics and better understand the outcomes.

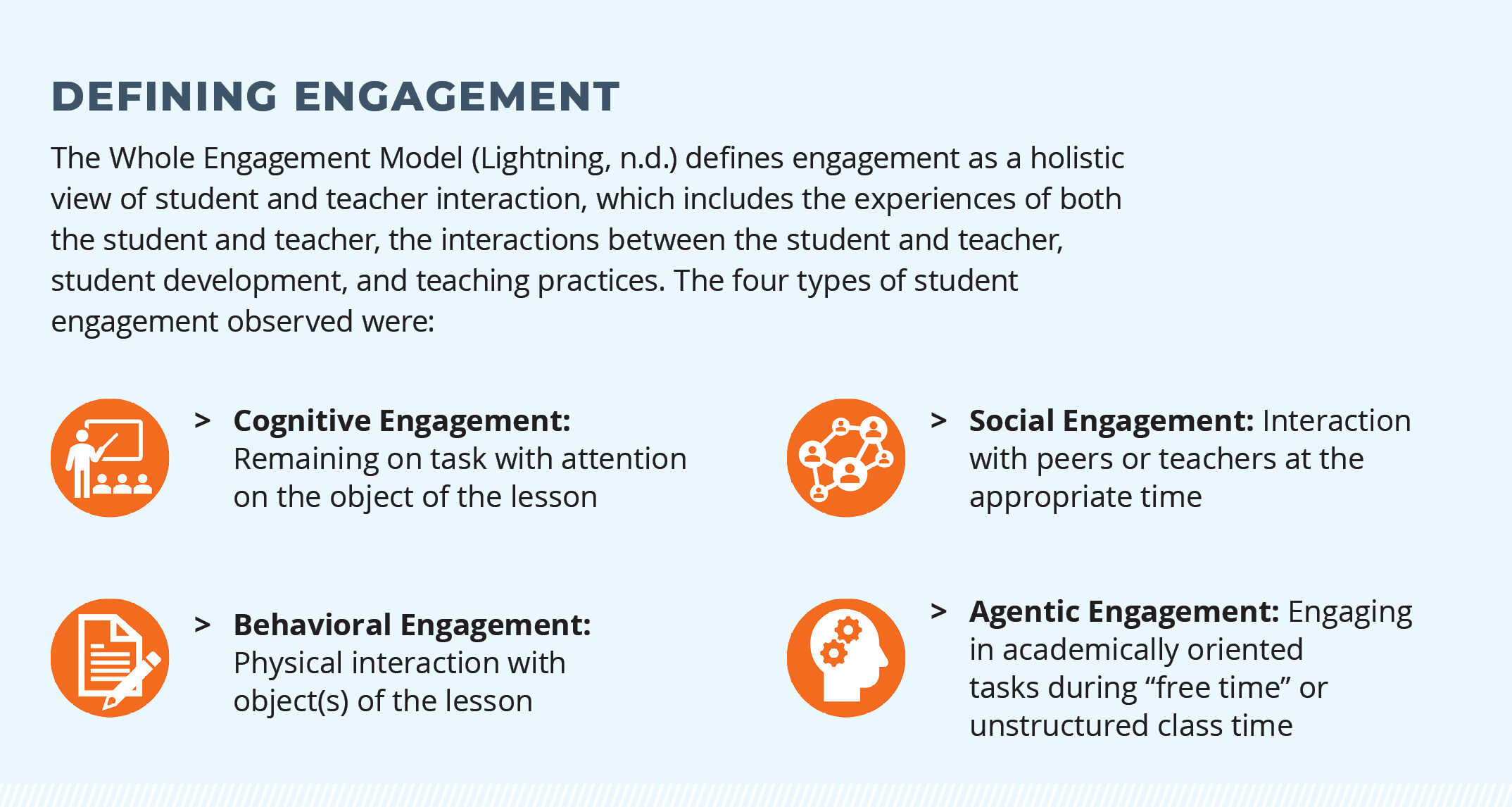

The original Glover Middle School remained operational during the construction of the new building; this opportunity was not lost on NAC’s team. Our researchers designed a study to explore how the new Glover Middle School would promote engagement compared to levels in the existing building. Observations were conducted in both facilities, examining engagement through four types: cognitive, behavioral, social, and agentic engagement.

As we compared the levels of engagement between the two facilities, our observations revealed higher levels of engagement in the new Glover building. The types of engagement showing the largest increase in percentage of overall engagement were Agentic engagement (+41%) and Behavioral engagement (+20%). Both of these forms of engagement have to do with student choice during structured and unstructured work times without direct instruction from the teacher. While we aren’t able to attribute this directly to the newly constructed school building, we are able to observe how the design supports these types of engagement.

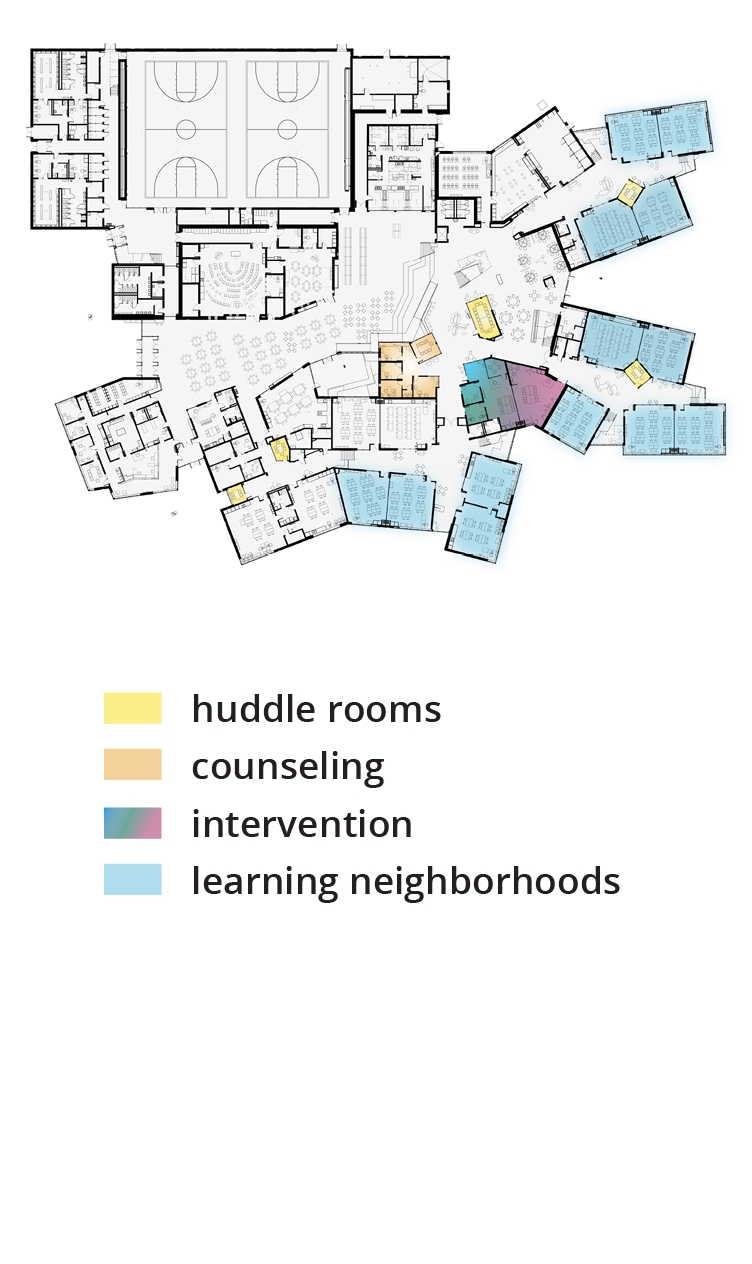

Glover Middle School contains six learning neighborhoods which are divided by grade level. Each neighborhood is a community within the school providing a home base and a place of connection for students within the larger school. Each classroom neighborhood is designed with ample space and work areas for students to spread out to work alone without distractions. Plentiful seating is provided around corners, under stairs, and other spaces distributed around the neighborhood for small groups to meet and collaborate both within class time and during breaks. Large expanses of glass create visually connected spaces, allowing students to work in a way that suits them while teachers maintain sightlines. Operable walls between classrooms facilitate separate classes joining together for special learning experiences, building excitement, anticipation, and ultimately a camaraderie amongst students and staff.

Glover Middle School’s Falcon Time program, an academic intervention and enrichment initiative, thrives in the new building. With spaces designed to support collaboration and flexibility, teachers are able to connect with peers and work with small student groups effectively. This targeted support has led to significant gains in test scores, in which Glover Middle School students outperformed 8 of 9 district peer middle schools in math and 7 of 9 district peer middle schools in ELA. The school's flexible spaces allow for quick adaptation to meet student needs, demonstrating how the built environment can engage students and ensure they achieve their learning goals. Due to the pandemic and other unforeseen limitations, the study did face some challenges, however qualitative staff stories and test scores align with the data.

Intentional support for Intervention

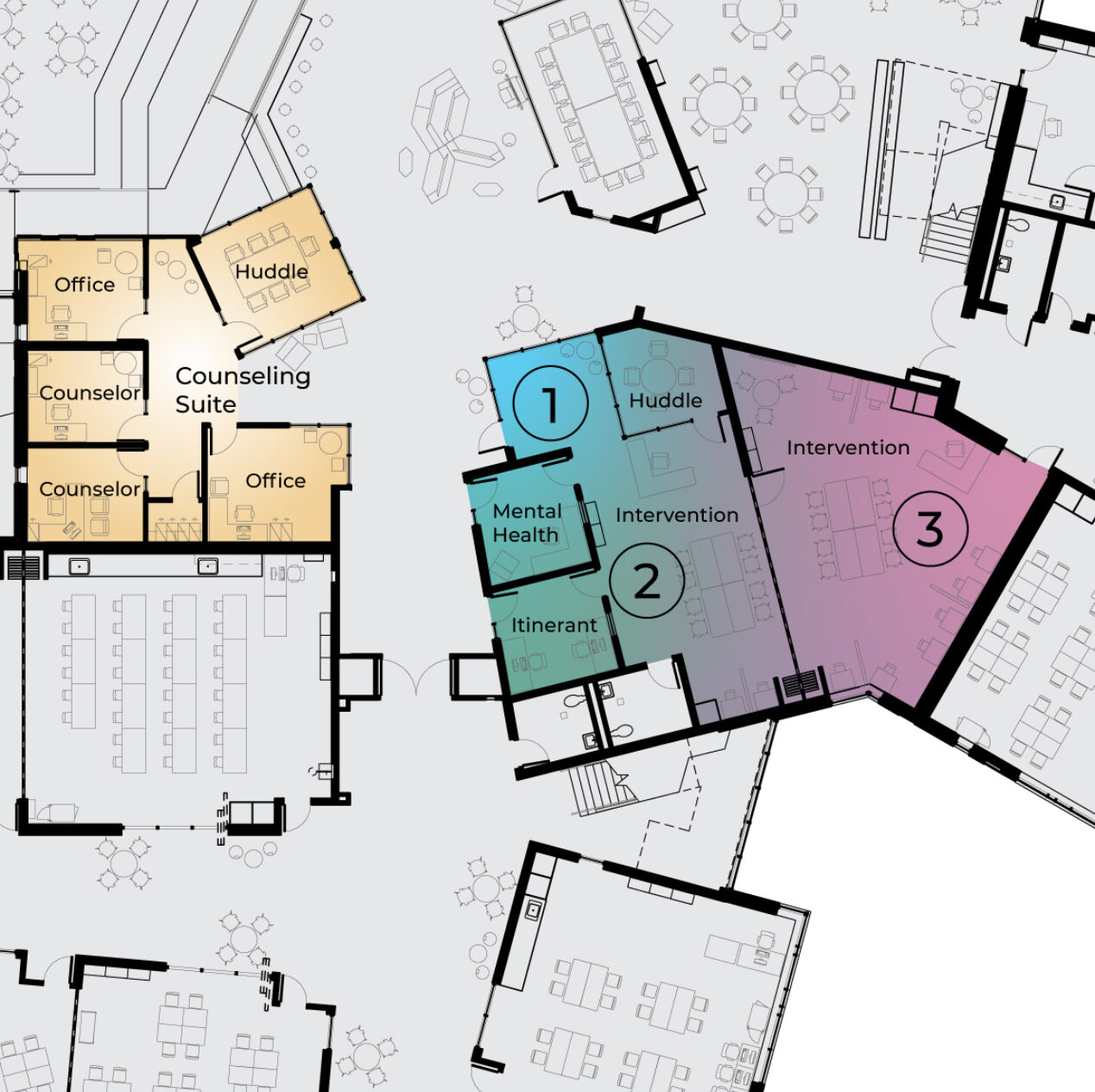

Engagement and academics are only two components of a healthy school culture. Prior to the construction of the new building, Glover had a robust intervention program cultivated from a multi-tiered support system (MTSS). However, it was challenging to engage with students in their environment and discuss disruptive behaviors or emotions that they might be experiencing without removing them from their classroom or community. Removal from their classroom fractured relationships between students and teachers. If the student had to leave the classroom neighborhood to work with an intervention specialist (interventionist), this could cause shame and mistrust within their community.

During the first seven months in the new building, 62 staff members throughout the school made 2,400 calls for support from an intervention specialist. Of those calls, 90% of those incidents were resolved in the neighborhood between teacher and student or with support from an intervention specialist. Only 10% of the calls resulted in a student needing to leave the neighborhood or classroom and access support outside of the academic neighborhood. The ability to support kids in their environment removes stigmas, improves the relationships between students and teachers, and ultimately reduces the amount of time the student is not focusing on school activities.

To keep students in their classroom neighborhood, we created intentionally designed zones to promote student choice in the learning environment and for focused conversation with students exhibiting challenging behaviors. One of these spaces is the huddle room located in each classroom pod. This multi-use space supports small group work, provides a place for paraeducators or specialists to work with students, and facilitates teacher collaboration. The transparent room also allows an interventionist to have a private conversation with a student or teacher while maintaining sightlines to the classroom. Small learning stairs near exterior windows, soft seating choices, and a bench under the stairs serve dual purposes. They enhance the learning environment by supplying a variety of choice for students and provide spaces for staff to connect with students in areas that support the different types of conversations that may occur during the school day.

Huddle rooms within the learning neighborhoods provide visible but acoustically secure spaces for student groups, intervention meetings, or instructor and student one-on-one meetings.

Holistic Connection, supported through data and research

The design of Glover Middle School is deeply rooted in the foundational concepts of connection and engagement, impacting not only its daily students but also the broader community. One key feature is the Family and Community Resource Center (FCRC), inspired by the successful model at Flett Middle School, as discussed in our previous article. Strategically located near the administration area, the FCRC serves as a hub for community programs, resources, clubs, and other activities that benefit the entire Glover community. When not hosting external programs, the space provides a welcoming environment for meetings with students and their families. By fostering community partnerships through the FCRC, the school strengthens its support network, benefiting both children and families. This comprehensive approach, rooted in enhancing connection and engagement, reflects a growing trend in communities nationwide. It underscores the transformative potential of learning environments in addressing the multifaceted challenges facing our youth. As we continue to measure success through data and narratives, it becomes evident that such holistic approaches are not just effective now but are also vital for the future well-being of our communities.