The Language of Learning Spaces: Designing to Support ELL Students

Architects and designers are continuing to increase our awareness of the diverse needs of students, and how the built environment plays a pivotal role in supporting the diversity of needs. Design considerations for programs like Special Education and Sensory Awareness have been getting more attention over the years, with school districts incorporating requirements into their education specifications to meet the needs of these students. However, one student population that is sometimes overlooked is English Language Learners (ELLs). State and federal mandates outline the requirements for ELL students so they can “participate meaningfully and equally in educational programs,” 1 however every school and school district supports their ELLs differently.

Getting to a Common Definition

Over time, English Language Learners, educators, and program classifications have evolved in an effort to distinguish between different approaches and different types of learning environments. For the sake of this article, we ascribe to the following definitions.

ELL (English Language Learner) or EL (English Learner): According to the U.S. Department of Education, an EL is an individual (A) who is aged 3 through 21; (B) who is enrolled or preparing to enroll in an elementary school or secondary school; (C)(i) who was not born in the United States or whose native language is a language other than English; (ii)(I) who is a Native American or Alaska Native, or a native resident of the outlying areas; and (II) who comes from an environment where a language other than English has had a significant impact on the individual’s level of English language proficiency; or (iii) who is migratory, whose native language is not English, and who comes from an environment where a language other than English is dominant; and (D) whose difficulties in speaking, reading, writing, or understanding English may be sufficient to deny the individual (i) the ability to meet the challenging state academic standards; (ii) the ability to successfully achieve in classrooms where the language of instruction is English; or (iii) the opportunity to participate fully in society.

ESL (English as a Second Language): formerly used to designate ELL students; this term increasingly refers to a program of instruction designed to support the ELL.

ELD (English Language Development): the term used for an academic program to assist all students whose primary language is not English.

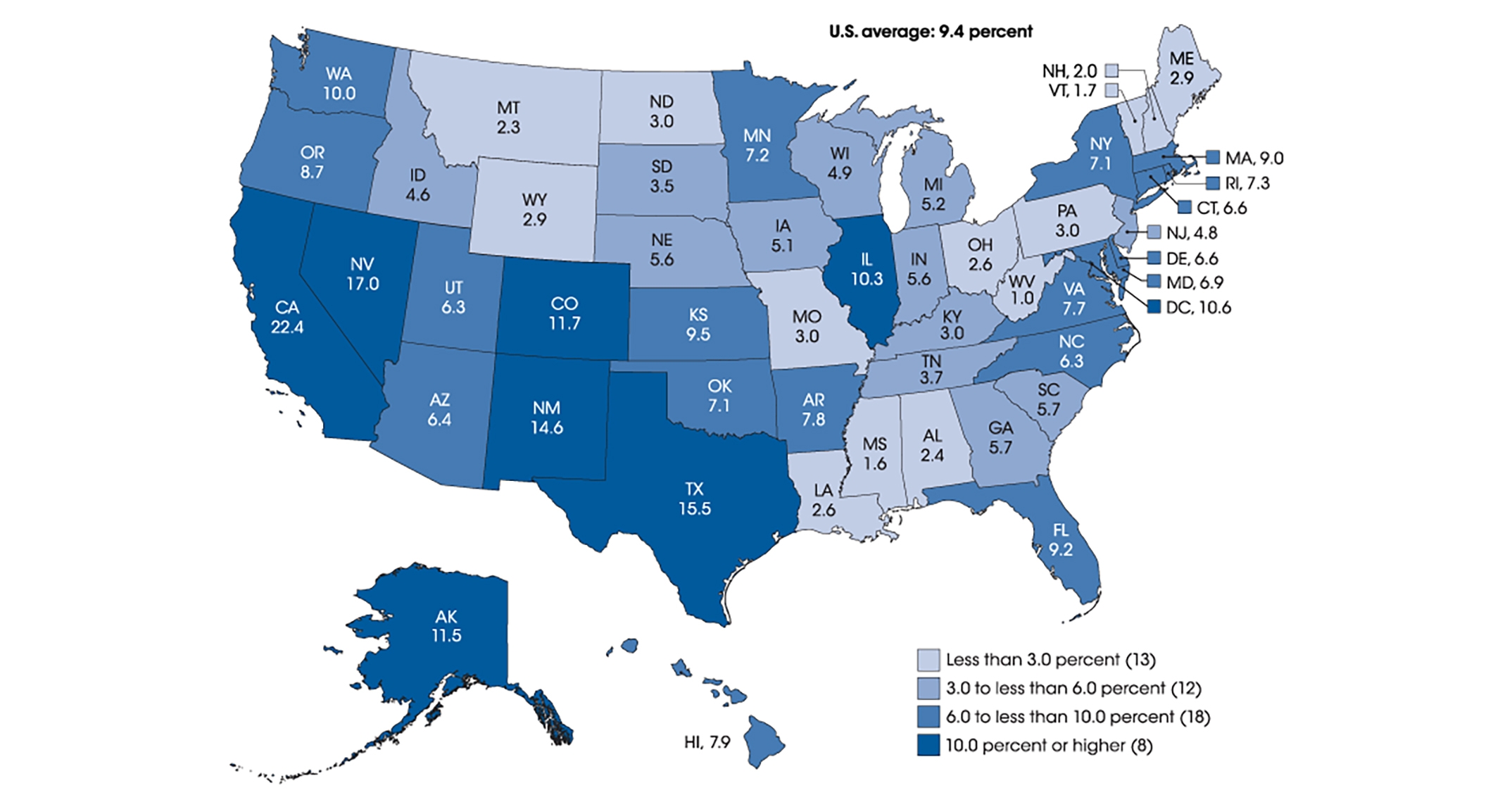

This map represents the percentage of public school students who were ELLs by state during the 2014-2015 school year. Source: US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD), “Local Education Agency Universe Survey,” 2014-2015

Different Approaches to ELLs

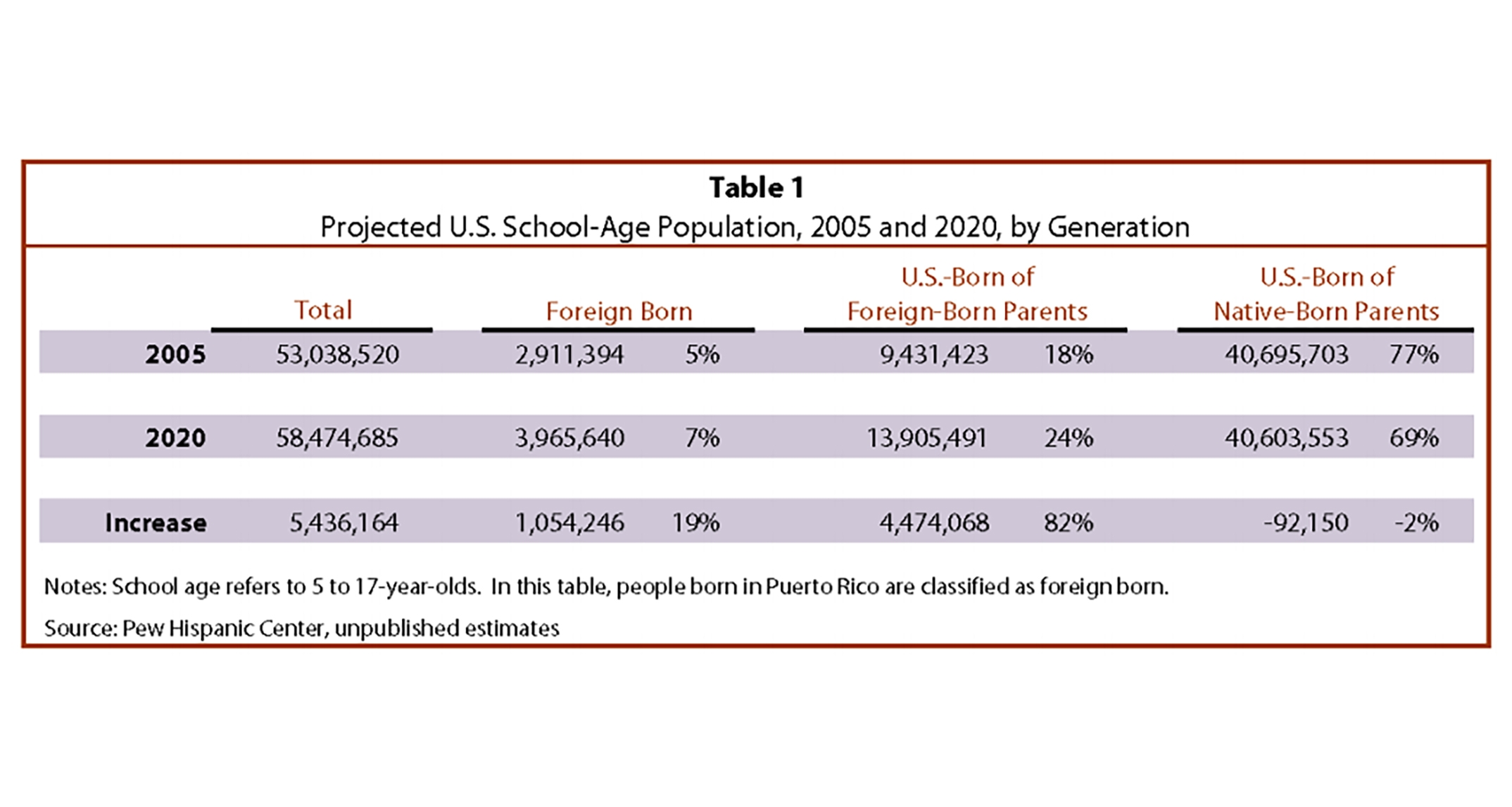

It is reported that around 10 percent of all public school students in the United States are ELLs—a large population that must be taken into consideration when developing school curriculum, as well as facilities/space planning. Some schools choose to immerse these students into their English-speaking environment with little or no dedicated break-out time for additional support or instruction. The teacher is aware of individual ELL levels and makes adjustments, whether it is where they sit or how lessons are given, in order to help with the transition.

On the other hand, some schools provide dedicated English language lessons in a separate classroom or space, typically with smaller groups of students at the same acuity level. In this model, the students are able to focus only on learning the language with peers in a similar situation.

Case Study: Wing Luke Elementary School

Seattle Public Schools has the largest population of ELLs in the State of Washington. 2 In addition to providing a comprehensive program to meet state and federal requirements, the district’s mission is to ensure the success of every student, family, and community, allowing them to thrive in our global society.

Wing Luke Elementary School boasts an extremely diverse and

multicultural community, where over one third of their student population

identifies as ELLs, and with many more students speaking a language other than

English at home. Because of this diverse population, Wing Luke is a Bilingual

Center School, which employs two full-time ELD teachers and five bilingual

instructional assistants. NAC is currently working on a new replacement

facility for the school.

Developing a successful design for the new school required working within the Seattle Public Schools’ education specifications, and identifying the importance of allocating spaces that meet the needs of ELL students and teachers. Kindergarten and 1st grade students are in collaborative classrooms where the pod teacher and the ELD teacher co-teach for part of the day. Other grade levels are taught in small groups during reading and math blocks. Bilingual instructional assistants tutor students and provide both academic and language support as needed.3 During class time, ELL students are immersed in the day-to-day curriculum, with the option to be pulled out for additional one-on-one sessions or group sessions as needed. For ELL students who need additional support completing homework, an after school homework club is also offered.

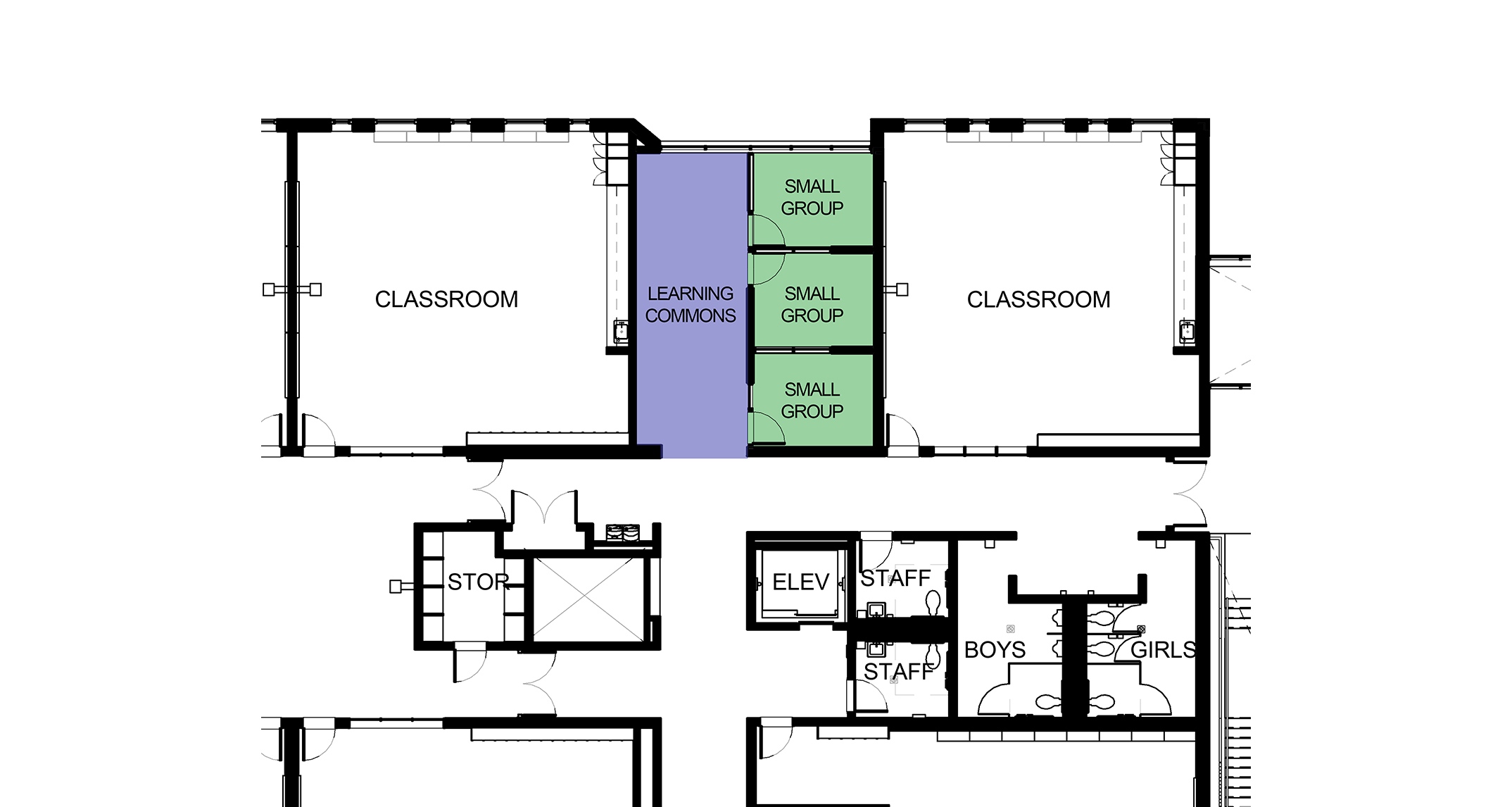

In addition to multiple larger collaboration areas placed throughout the school, a smaller learning commons and adjacent to breakout rooms provide areas for a range of ELL instruction. This learning commons is placed prominently at the intersection of grade level pods, providing visibility and access to the rest of the school.

With such a variety of multi-cultural influences (languages that are currently spoken at the school include Somali, Vietnamese, Chinese, Spanish, Cambodian, and Cham), the new school is designed to celebrate these diverse cultures and promote a sense of inclusivity for students and the community, where the school is a family. This is exemplified through a large central courtyard that is adjacent to the main lobby. The courtyard can be accessed by the commons and through some of the classrooms. It provides a space where the community can gather, and can be used by every student and family to make them feel welcome and establish a sense of belonging, regardless of their background. Multi-lingual wayfinding and graphics throughout the building further celebrate the diversity of Wing Luke students.

The central courtyard at Wing Luke Elementary provides a welcoming place for students and their families to gather, and support feelings of inclusion and belonging.

Each Student’s Experience is Unique

Each ELL student has different experiences associated with learning the English language. Inspired by our work on Wing Luke, we spoke with a few people around our office to gain some context and information on their own personal experiences. We were able to establish some similarities between their stories, and some approaches to ELL programs that can help students learn better. Some of these included:

- Full immersion into an English-speaking environment;

- Socializing with fellow classmates creates inclusion and connection;

- Teachers using visual aids as much as possible when teaching a lesson;

- Working with smaller groups in class;

- Having opportunities to look at a lesson before hand and/or get additional help afterwards.

“I learned English in Sydney, Australia, where my parents immigrated when I was 10. I took after-hours ESL courses during 5th and 6th grade at Marist College North Shore while my friends played cricket and rugby outside. Three times a week, I used to walk up six flights of narrow spiral stairs to my ESL teacher’s attic office at the top of the school’s gothic bell tower. I still remember to this day, looking out through the limestone traceries of tower windows to see the blue Sydney Harbor in the distance, the iconic Harbor Bridge, and the curious, glistening, glazed white tiled roofs that looked like dancing quarter moons. It was my favorite thing to see on my way to class. I believe my English learning is intrinsically tied to a place, a locale, and a childhood magic of seeing the Sydney Opera House.”

- John Kim, Senior Associate, NAC

Conclusion

There are many reasons why children become English Language Learners. Identifying, supporting, and celebrating multiple languages and cultures is the key to fostering a global society, and promoting a global future.

Just as John Kim expressed when he recounted his experience as an ELL, a connection exists between learning and the environment in which it takes place. We believe that the needs of ELL students should become part of the nomenclature of educational design. We must create spaces where these students not only thrive, but can establish their own sense of identity and build community, regardless of their native language or culture.

Additional Resources

https://www.cultofpedagogy.com/supporting-esl-students-mainstream-classroom/

https://www.edutopia.org/blog/esl-ell-tips-ferlazzo-sypnieski

References

1 https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/ellresources.html

2 https://www.seattleschools.org/departments/english_language_learners